Suzie thanks Kim for the gift of a South Africa outfit from Build-a-Bear in Cape Town.

Joe our Wine Steward (right) in the Filipino crew show.

This was a dance where glasses of water are spiraled with no spills.

This dance was done on the narrow seat of a bench.

The Assistant Dining Room Manager dances between moving bamboo sticks

The end of the Filipino crew show featured this patriotic image.

Squeekie does one of the “Sports of Call” activities.

While we were taking pictures around the ship we found Iris painting a watercolour.

Squeekie in Rotterdam’s aft stairwell checks a lion’s teeth.

We were invited into the special crew celebration of Willem Regelink’s 40 years with HAL

Captain Olav (center) and Hotel Manager Henk Mensink (sitting right) say some nice words about the muck-loved Willem.

Willem Regelink at his special 40th anniversary celebration.

Members of the housekeeping staff also had kind words for Willem.

Willem cut a special cake . . .

. . . and was presented with some framed artwork commemorating his career.

Squeekie took this picture of Moss and his colleagues of the “Orphans” trivia team.

Lori runs one of the indoor “Sports of Call” events.

A panorama of the port side downstairs of the LaFontaine Dining Room.

The forward port section of the Lido dining area; this is where ice cream was served.

The Lido (deck eight) swimming pool in the centre of the ship.

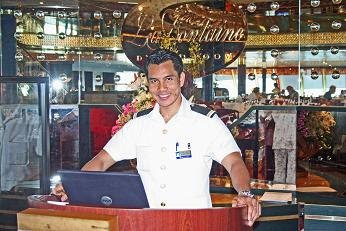

Presti, our Dining Room Assistant Manager, at his command post; thanks for the great care, Presti!

Tea time in the LaFontaine Dining Room on Deck Five.

Bartender Henry P. at the Crow’s Nest Bar.

All of the Isles du Salut (Devil’s Island on the right) appeared through the morning haze.

The pilot skimmed across the waves to guide us in to our anchorage . . .

. . . which hove into view; how innocent these islands looked from a distance!

Seven miles away on the mainland we could see the French launch complex.

Moss waits to go ashore to this historic place . . .

. . . as does Squeekie!

Squeekie is eager to take the tender over to the island.

One of Rotterdam’s tenders unloads curious guests on Isle Royale, formerly the administrative headquarters of the penal colony.

Squeekie went on ahead up the path to the buildings on the top of Isle Royale.

We could see Rotterdam in the sun just offshore; nobody was going to give us 20 years on Devil’s Island!

As we walked up the hill, we could hear monkeys . . .

. . . and we could see some of them, too!

This one just stared back at us; was he posing?

At the top of the island were buildings, ruins, and a cemetery.

In the cemetery were women and children only.

These were houses for the administrators and guards.

There was a chapel . . .

. . . inside of which there remained art done by the prisoners.

This was an administration building, with the French flag hanging limp in the humidity.

There were some ruins . . .

. . . and even a lighthouse.

This reservoir, now filled with green water plants and iguana lizards, was dug by prisoners using only spoons!

Moss took this picture of Squeekie photographing the iguanas . . .

. . . and the iguanas looked at us; I wonder what they were thinking.

Among the other animas were peacocks . . .

. . . pheasants . . .

. . . a rodent known as an agouti, . . .

. . . and more iguanas!

On the back side of Isle Royale Squeekie had her picture taken with the actual Devil’s Island in the background . . .

. . . as did Moss . . .

. . . and here it is, the actual Devil’s Island itself, just yards away . . .

. . . but difficult to get to, or escape from, because of riptides . . .

. . . so the French guards got over on a cableway, of which only one pillar remains.

This is Alfred Dreyfus, Devil’s Island’s most famous prisoner . . .

. . . and this is the hut in which he lived for five years in the 1890s.

The French still patrol these islands very closely with their “Maritime Gendarmarie.”

In the late afternoon we departed from these historic and tragic islands.

One Hundred and Second Day (Friday, May 1, 2009)-- Today was the first of four days at sea as we sailed northwesterly towards the coast of South America and French Guyana. There was nothing much to report on today except to say that some passengers are beginning to prepare for the end of the trip by packing, or at least to talk about it. This has made us angry, especially Squeekie, for we have loved this circumnavigation and are nowhere near ready for it to end. Tonight’s show included a female comedienne who was really funny, but that’s about the only detail of the day that I can describe. After dinner was completed the Filipino Crew Show was featured, and it was very well done. Squeek and I liked the fact that we knew by name many of the performers because we have gotten to know the crew so well. We were particularly bemused (I have deliberately selected that word) by the appearance of our wine steward Joe in drag as he played the part of a girl in several of the dance scenes. We suspected that that was the direction in which he swung, and now we are certain.

One Hundred and Third Day (Saturday, May 2, 2009)-- Today was the second of our days at sea travelling northwesterly towards French Guyana. We spent a little bit of time up in the Crow’s Nest, and Squeekie did her usual Sports of Call events while I spent another trivia episode with my colleagues of the “Orphans” team. Today we had planned to spend some time taking pictures around the ship, but we seem to have sailed into a rain storm so the outside pictures were cancelled. Still, we did take pictures in a number of the public areas, and that brought us into a special event of real interest.

As we came to the upstairs entrance to the LaFontaine Dining Room to take pictures, the Manager/Maitre’d Tom Grindley beckoned us to come inside. Set up at the back of the upper deck was a very large sign honouring Willem Regelink, the Chief Housekeeper, for his fortieth year with Holland-America, and Tome encouraged us to join in the festivities. We knew of Willem, of course, although he was not one of the first-name basis acquaintances we have made on this cruise, and we were happy to have been invited to join in this very special party.

As we waited for the event to start up we saw that most of the ship’s senior officers were there, so thic clearly was an important recognition. Captain Olav and Henk Mensink (the Hotel Manager) kicked off the festivities with some kind remarks about Willem and his career history. Several gifts were presented to him as well, and then Captain offered a toast. When these recognitions were done, each one of the cabin stewards shook his hand before they had to return to their duties. The reception wasn’t long or overdone, but it obviously came from the heart. As for the gifts he received, aside from the service award given by the company (which had been given by Stein Kruse earlier in the voyage while we were on our China overland trip), the housekeepers contributed to get a very nice gold watch, and one of the artists among the crew had drawn up cartoon pictures that were framed and signed by all of the staff. This recognition was clearly “from the heart” and not just done by the numbers. Squeekie and I were very impressed by the personal sincerity toward Willem offered by all from Captain on down to the lowest housekeeper, and we were glad to have had the opportunity to see it at first hand.

In the afternoon of this rainly, cloudy day I woked on the blog in our stateroom while Squeek did our personal laundry. Ugh, what a drab afternoon, but I guess these will crop up now and then even on such a dramatic cruise as we have been enjoying!

One Hundred and Fourth Day (Sunday, May 3, 2009)-- This was the third of the four at sea days we must have on our way to French Guyana. It rained all day long and it was difficult to spend time doing our blogging and journaling work. We enjoyed the special French Tea up in the LaFontaine Dining Room in the afternoon, which was quite nice, but otherwise the day was blahhhhhh. Even the dinner tonight was less than remarkable, an amazing outcome given the effort that the cooking staff makes every day to feed us so well! It was yet another formal dinner, and we hosted at our table another couple we have befriended on this trip, Neil and Marsha Steinbrenner, who live in Laguna Woods in Orange County. That was the only really nice part in an otherwise very uneventful day.

One Hundred and Fifth Day (Monday, May 4, 2009)-- This was yet another at sea day. It was better than the previous because the sun was shining, but not otherwise of real interest.

One Hundred and Sixth Day (Tuesday, May 5, 2009)-- Today began like the previous several at sea, but around 10 a.m. the entire ship was galvanized as land hove into view off the port side—South America (French Guyana) and the island group popularly known as Devils Island, which once upon a time had been the infamous French penal colony. We had finally arrived at our first port of call in the Western Hemisphere since we had left the Pacific coast of North America nearly four months ago!

A bit of history about this historically infamous place-- Devil’s Island (Isle du Diable in French) is the smallest and northernmost island of the three Salvation Islands (Isles du Salut) located about seven miles off the coast of French Guyana. (The other two islands in the group are known as Royal Island [Isle Royale] and Saint Joseph Island [Isle du St. Joseeph]. These islands were a small part of the notorious French penal colony in French Guyana until 1952.

In 1763, some 12,000 French settlers were induced to accept offers of free land in the El Dorado of Guiana, on the northeast coast of South America. These 12,000 arrived expecting to scoop sacks of gold and diamonds from the ground, but they were unprepared for the tropical climate and proceeded to die by the thousands. Lacking proper dwellings, they were caught in drenching storms; after the rains, they reeled through the steaming jungles, were caught in floods, and were assaulted by clouds of malaria-bearing mosquitoes. Only about 2,000 of the original 12,000 survived the first year, and these were saved by taking refuge on three islands just a few miles off the mainland coast of Guyana. As a result, these islands became known as the Islands of Salvation (Isles du Salut): Isle Royale, Isle St. Joseph and Devil's Island. This latter was the smallest of the three, only about 34 acres, and so called because it is separated from Royale by a vicious tide.

By 1775 there were 1,300 whites and 8,000 slaves in all of French Guyana, and thousands of blacks fled into the bush where, for more than a century, they formed renegade bands and made forays against the plantations and white settlements: killing, looting and liberating other slaves. These escaped slaves, and their descendants, constitute the so-called “bush-Negroes” of modern Guyana. The slaves of French Guyana were emancipated in 1794, only to be re-enslaved when the fortunes of the colony dwindled. A second emancipation occurred in 1848. However, by this time the reputation of Guiana was so evil that white colonists could not be persuaded to emigrate there. Napoleon III decided to solve the problem by transporting political prisoners to the colony, which would henceforth be a penal settlement.

The main penitentiary, and headquarters of the Penal Administration, was situated on the outskirts of the mainland capital city of Cayenne. The next largest prison camp was at St. Laurent; also on the mainland. Those sentenced to a period in the dreaded solitary cells went to Isle St. Joseph. Upon release from solitary confinement, a convict had to spend a minimum of six months in the Crimson Barrack on Isle Royale. The worst prisoners were assigned to the tiny island surrounded by sharks and harsh tides known as Devil’s Island.

While the penal colony was in use (1852-1952), the inmates were everything from political prisoners (such as 239 republicans who opposed Napoleon III’s coup d’etat) to the most hardened of thieves and murderers. A great many of the more than 80,000 prisoners sent to the harsh conditions at the disease-infested penal colony were never seen again—perhaps just one fourth of that number ever returned to France. Other than by boat, the only way out was through a dense jungle. Most of the atrocities of Devil’s Island took place in the timber camps on the mainland, where the prisoners were forced to work in water up to their waist, assaulted by malarial mosquitoes, baked by the sun. They were underfed and overworked in their daily task, to cut one cubic meter of wood. Although the convicts in the punishment camps were made to work naked except for shoes and straw hats (to minimize escapes), there are cases on record of men running into the jungle, unclothed and unarmed. In spite of fantastic odds, such escapes occasionally did succeed—a feat that became increasingly difficult as the years passed.

At first the neighboring government of Dutch Guiana provided sanctuary to those who successfully crossed the piranha-infested Moroni River. Later, as a result of atrocities committed by the escaped prisoners, the Dutch were less willing to help the prisoners to escape and began returning them—or letting them die in the jungle. A Dutch soldier, stationed on the Maroni River, once heard horrible screaming from the river after dark and went to investigate. About 25 feet from the bank he saw a convict struggling forward, with the water boiling beneath him. Fist-sized chunks of flesh were torn from his arms, face and chest as the piranhas skeletonized the convict before the soldier’s eyes. Other escapees were picked clean by army ants in the jungle; several were cannibalized by fellow escapees.

Over the years some famous persons were imprisoned at the penal colony, and several of them became famous for attempted or successful escapes. The horrors of the penal settlement first became notorious around the world in 1895 with the publicity surrounding the plight of the Jewish French army captain Alfred Dreyfus who was wrongfully convicted of treason and was sent there on January 5th. In 1899, following a passionate campaign by his supporters, including leading artists and intellectuals like Émile Zola, Dreyfus was pardoned by President Émile Loubet and released from prison. Clément Duval, an anarchist, was sent to Devil’s Island in 1886. He was sentenced to death but instead performed hard labor. He contracted smallpox while on the island. He escaped in April 1901 and fled to New York City, where he remained for the rest of his life. He eventually wrote a book on his time of imprisonment called Revolte.

Prisoners in the penal colony referred to the system as the “dry guillotine.” The first appearance of that term in English came in June 1913 in a 14-page article in Harper's Magazine titled “Cayenne-the Dry Guillotine,” written by Charles W. Furlong. The article carefully detailed the cruel and often intentionally lethal conditions of life for bagnards (prisoners) in French Guyana and listed by name several specific examples of young men doomed to live out their lives in this hell on earth.

René Belbenoît, a veteran of the First World War, stole some pearls and was tried and sentenced to 8 years in 1920. He was sent to Devil’s Island. Belbenoît attempted to escape on a log canoe up the Maroni River, but was recaptured and sent to solitary confinement. In 1930 he was given an one year pass from the colony and spent this year in Panama working as a gardner. However, in 1931 he decided to return to France; he was re-arrested for this action and was sent back to French Guiana. After spending some time in solitary confinement on St. Joseph’s, he was released on the the mainland of French Guyana as a “libere,” that is, free of prison but not permitted to leave French Guyana. In 1935 Belbenoît started his escape which would finally finish in Los Angeles two years later. In 1938 he published his book Dry Guillotine, a memoir about his time in prison.

Henri Charrière’s bestselling book Papillon, first published in 1969, describes a supposedly successful escape from Devil’s Island with a companion, Sylvain, using two sacks filled with coconuts. According to Charrière, the two men leapt into heavy seas from a cliff and drifted to the mainland over a period of three days. Numerous aspects of Charrière’s account were challenged by French journalists or prison authorities, and it was claimed that a significant number of the incidents recounted in his book were invented or were experiences of other prisoners which Charrière had appropriated. I cannot help but wonder what kind of critic could sneer at a man who has braved the Atlantic in a flimsy raft made of two flour sacks sewn together and filled with coconuts? During his nightmarish escape he was at the mercy of the tides and had very little in the way of provisions. His determination to escape at all costs illustrates a human spirit that would rather suffer than endure life on the “islands of death,” as the prisoners called the penal colony. Despite the criticism, Charriere’s story remains, in print and then as a movie, the most famous of all accounts of the horrors of Devil’s Island.

In 1938 the French government stopped sending prisoners to Devil's Island, and in 1952 the prison closed forever. Most of the prisoners returned to metropolitan France, although some chose to remain in French Guyana. In 1965, the French government transferred the responsibility of most of the islands to the newly founded Guyana Space Centre. The space agency, in association with other agencies, has since had the historical monuments restored and tourism facilities added; the islands now welcome more than 50,000 tourists each year.

Well, after all of this pain and escape, it is back to our day at this place of horror-- The islands as seen from Rotterdam appeared too beautiful to have endured the history that is theirs. Squeekie and I watched from Deck Six Forward as we approached, and took some nice pictures of these coconut tree-covered islands. We anchored in the appropriately-named Baie des Cocotiers (Coconut Bay), where we even saw coconuts in their husks floating on the bay water, and before too much time had passed the tenders were at work ferrying passengers over to the main island in the group (and the only one we got to visit), Isle Royale, which had been the administrative centre of the penal colony, and had the most surviving buildings anyway. We had a late number (Squeekie remembers it as thirty-four), so we had a while to wait for our turn, and as we waited we watched the tenders moving up and down on the waves in relation to the ship’s loading platform (which folds down from the side of the ship when needed).

Eventually our number was called and we went down to “A” Deck to board the tender. By this time it had begun to cloud over and I was afraid that a rain storm in addition to the rough waves would prevent us from getting ashore. Fortunately, we did make it over to the island, and landing at the dock on Isle Royale was not nearly as rough as boarding the tender offshore had been. The rain was fine and short, and by the time we were on the island the sun had returned and the humidity was rising.

We were ashore on this infamous place. What was to be seen? I was hoping to visit where Alfred Dreyfus had been imprisoned, but soon learned that he had been placed in a hut over on the actual Devil’s Island, the tiny islet to the northeast of Isle Royale. Squeekie, full of energy as usual, took off up the ramp-road which led up to the plateau on the top of Isle Royale. I followed much more slowly. There were a myriad of coconut palms on the island (actually on all three), and many had dropped nuts on the roadway—one had to be aware of the possibility of a fall all the time. The good news about the palms was that they formed a thick canopy which shaded one from the worst of the sun, although nothing could be done about the humidity. That is one of the downsides of being a Californian, I guess, the reality that, unlike Floridians and other southeasterners, we are not accustomed to high humidity and we find that type of weather to be very debilitating. Still, I was able to walk my way slowly up the ramp to get to the top where all of the historic buildings are grouped. On the way, I heard and occasionally saw the monkeys which play in the trees.

At the top of the island’s plateau I began snapping pictures of the surviving buildings, although without a tour guide it was difficult to know what functions they once had had, and in some cases, what they were doing now. Squeekie had found and photographed a children’s cemetery, always a poignant thing to see; then we joined up to photograph what we could, both ruins and local wildlife. At one place we came across a large, rock-lined hole which looked like it might once have been a water storage place of some type, although now what water it had in the bottom was filled with bright green plants of some type, and through which were walking very large iguana lizards. I have since learned that this was indeed the reservoir supplying the buildings on Isle Royale, and that it had been excavated by prisoners in the early days of the island’s use as a prison, and that it had been excavated by them using only TEASPOONS! Talk about punishment!

The former warders’ mess has been converted to a hotel and restaurant although I find it difficult to understand why anyone would wish to spend many vacation days here; the island is beautiful, but there is only one beach and the water way is too turbulent for swimming—to say nothing of the sharks in the waters just offshore. However, when I got to one place overlooking the ocean on the southwestern side of Isle Royale I looked out and could see in the distance the huge hangars which hold rockets. When the French and the European Space Agency launch from the site on the mainland in French Guyana the ships travel right over the isles as they rise into orbit (or whatever). So I guess that there is an additional attraction for people to stay on this island.

We also visited the little museum and I found it interesting despite the fact that—in typical French cultural arrogance—the signs were exclusively in French. On our entire trip, the only time we saw museum signs only in the local language to the exclusion of other languages spoken by a majority of the tourists was in French colonies. Ah, well! Fortunately, there was a guidebook available in English which we did pick up.

After the museum we walked back down to the dock. I chose to rest my sore feet there and photograph the monkeys and other curiosities there while Squeekie continued her exploration of Isle Royale by going to look at the ruins of the cableway which once ran over the rough waters separating Isle Royale from Devil’s Island. Eventually we joined back up and took the tender back out to the Rotterdam. Oh, what a pleasure it was to return to the niceties of that mighty ship after seeing the horrors which had been imposed on the bagnards (prisoners) of the penal colony.

This evening was held a Cinco de Mayo celebration aboard the Rotterdam, but I chose to ignore the event. It is NOT my holiday, and, like many multi-generational Californians (and Texans, New Mexicans, and Arizonan, too, I’m sure) I am becoming VERY sensitive to the imposition of Mexican culture upon us as the illegal Mexican population swarms in without any apparent effort to stem the tide. Oh well . . . . Now we are headed northwesterly towards out next stop, the Island of Trinidad, the southeasterly cornerstone of the Caribbean island chain.

Before I drift off to sleep in our delightful stateroom, however, I wish to think a few last thoughts about the penal colony known as Devil’s Island. Those of you who know me well, either as family, friend, or teacher, already know that I am as Francophobic as I am Anglophilic—in other words, I dislike the French as much as I love the British (who are, after all, my maternal ancestors). With that as a foundation, perhaps then you can understand why I wonder how and why a nation which claims repeatedly to be the most sophisticated on earth also maintained one of the cruelest, most heartless prisons in all of history—close in many respects (except numbers imprisoned) to the concentration camps maintained by the Nazis. This is nothing short of an incredible paradox! In addition, another paradox is presented by the prison camp of Devil’s Island: continuing public interest in the stirring picture of forsaken men, no matter that they are criminals, taking up the challenge and attempting to “beat the system” against incalculable odds. Escape from Devil's Island seems to appeal to the primitive instincts of people everywhere who, though socialized and urbanized, inherently regret the loss of individuality that appears to accompany modern society.

I hold up the story of Rene Belbenoit as a classic example. (I knew about him when I arrived at Devil’s Island, but have researched more about him since I returned home.) This convict (perhaps more correctly “this victim of the French penal system”) was a small man who weighed less than 100 pounds. He spent 15 years in the bagne (Devil’s Island penal colony) before finally escaping by sea. He made his way along the entire northern coast of South America, lugging a 20-pound manuscript wrapped in oilskin, his condemnation of the horrors of the French penal colony. This diminutive convict made it to Panama, where he spent nearly a year living with a friendly tribe of Indians. He then pushed on through the jungles of Honduras and Guatemala, eventually to Mexico. When he crossed the border into the United States he was toothless, emaciated and broken in health. He settled in Los Angeles in 1937, and his manuscript made its way to E.P. Dutton & Company. Published in 1938 under the title Dry Guillotine, the book went through 14 printings in less than two months. To be sure, it is not as well written as Charriere’s Papillon, but that is just a reflection of Belbenoit’s own level of education. Without question, Dry Guillotine is one of the remarkable books of all time-—a testimony of despair, fortitude, and courage.

1 comment:

Thanks Bill for finishing up your trip to conclude the journey. I have so enjoyed reading Lynn's journal as a complimentary writing to your descriptions. Glad to have you home!

Post a Comment